Tim Benton_Le Corbusier and the vernacular plain

The house known as ‘Le Sextant’ designed by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret for Albin Peyron has been little discussed in the technical literature (Figure 1 and Figure 2)[1]. Pushed back from the street as far as the plot allowed, the house carefully preserved the existing pine trees. None of the Five Points for a New Architecture, coined as recently as 1927, appear to be visible here.

Figure 1 View of ‘Le Sextant’ from the North West (the street side)_copyright Tim Benton

Figure 2 ‘Le Sextant’ viewed from South_copyright Tim Benton

Concrete pilotis, the free plan, free façade, long windows and flat roof with roof garden have been replaced by wooden posts and beams, rubble walls, a rigidly compartmented plan, discreet windows and a double-pitch roof. Le Corbusier could claim, in the Ouevre complete (volume 3) that this was due to a very restricted budget and the use of a local mason, but this is not the end of the story [2]. Le Corbusier had always considered the vernacular and the classical to be on a par. When he made his long voyage to the East in 1911, he wrote as much on the vernacular buildings of the Balkans, Greece and Italy as on the famous temples of Greece and Rome. As a young man in the Swiss watch-making town of La Chaux-de-Fonds, he had turned away from the industrialised city, with its apartment blocks and grid of streets, to seek out the high slopes of the Jura, spending several months each winter snowed into a vernacular farm-house with its tué (a snug built around the fireplace)[3]. Following his move to Paris in 1917 and throughout his Modernist period in the 1920s, Le Corbusier retained his fascination with vernacular architecture, sketching details and taking measurements on his travels [4]. His very important book La Ville Radieuse begins with the words: ‘I am attracted to a natural order of things’ and contains many images of natural objects and vernacular architecture. And Bruno has written about Le Corbusier’s ‘discovery’ of natural materials around the time of the Maison de Mandrot (1929-32) and the possible links with the regionalist style [5].

For Le Corbusier, no architect could match the judgement and skill of the humble peasant who builds his own house around his daily actions [6]. He shared many of the ideas of the Austrian critic and architect Adolf Loos, who famously declared ‘Peasants have culture… architects have no culture’ [7]. By this, he meant that architects had been trained in a set of artificial skills –drawing plans and elevations – divorced from the real practice of building, the skills of construction and a respect for materials. Furthermore, despite the series of Purist Villas he designed for his clients in the 1920s, his own idea of a perfect vacation was an unbuttoned existence in the open air, living in and around a modest wooden house or cabin (Figure 3). For several years, from 1928, he had taken his summer vacation on the Bay of Arcachon near Bordeaux, staying in a wooden guest house at Le Picquey.

Figure 3 Postcard of Villa Berthe, Bassin d’Arcachon, in Le Corbusier’s collection, as an object of admiration. (FLC L5(5)35)_copyright FLC_ADAGP

Le Corbusier’s moving account in Une Maison un Palais of the fishermen’s houses in the pine forests of the Bassin d’Arcachon is his most heart-felt piece of writing on domestic architecture (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Amédee Ozenfant, sketch of fisherman’s hut on the Bassin d’Arcachon, illustrated in Une Maison un Palais, 1929.

Le Corbusier noted ‘the isolation, the separation from the rest of the world’ of the tongue of sand-dunes, between the lagoon of Arcachon and the Atlantic. The fishermen, who worked there in the summer, ‘only came there with the idea of living ‘from day to day’. This precariousness puts them into the paradigmatic situation of the house builder; they are making a shelter for themselves, somewhere to live, no more, in all simplicity and honesty. They are carrying out a pure programme unencumbered with claims to history , to culture, to the taste of the day. They’re building a shelter, somewhere to live, with the materials that come to hand [8]. And suddenly, says Le Corbusier, he realized that these houses were Architecture (or as he puts it, they were ‘palaces’). There are other signs of Le Corbusier’s preference for the most simple and primitive conditions for relaxing and living in the summer.

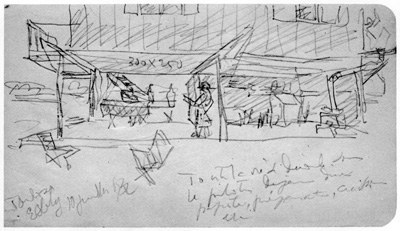

Figure 5 Sketch of rented vacation home at Esbly, 10 July 1932 (Sketchbook B6, Le Corbusier Sketchbooks, MIT, vol 1, p.389)

On 10 July 1932 he sketched a wooden shack, raised on stilts, rented by friends of his for a vacation (Figure 5 and Figure 6). He noted: ‘life enfolds entirely under the pilotis…’ and he clearly considered this casual existence idyllic [9]. And in his book La Ville Radieuse (1935) he illustrated the interior of one of the traditional stone houses which his friend Jean Badovici and his then partner Eileen Gray had converted with the following captions: ‘In Vézelay, 16th century and modern times and modern people…Why this astonishing freedom?… Why this sweeping generosity?… and this intimacy?… Because a proper human scale (that which has the true dimension of our gestures) has conditioned each thing. There is no longer old or modern. There is what is permanent: the proper measure [10]. And in the text he attacked the Existenzminimum mentality which he had helped to promote:

“The minimum home, as it has spread so tremendously these past few years in Germany, in Czechoslovakia, in Poland, in Russia, is no longer a place to live in: it is a cage. It is harmful, it is inhuman, it imprisons life within minimum limits, life that needs room” [11].

Alvar Aalto and many other Modernist architects, never lost their enthusiasm for vernacular architecture and, in a sense, measured everything they did against this standard [12]. From 1929 Le Corbusier had begun to try to incorporate some of these values in his own architecture, just as he had already abandoned the geometric discipline of Purism for a more voluptuous and earthy style of painting [13]. He designed a house in stone and wood for a Chilean friend Errazuriz in 1929 and built another for his Swiss friend and patron Hélène de Mandrot (1929-31). He began to understand the vernacular as being the secure link between man and nature, the direct expression of instinctual human needs, uncontaminated by abstract reasoning. Above all, it was Pierre Jeanneret who was becoming increasingly fascinated by vernacular architecture. With Charlotte Perriand he spent two years (1934-5) photographing and surveying old farm houses in the Jura mountains [14].

Alongside the rediscovery of vernacular architecture and the simple life, Le Corbusier and Pierre became very interested in the aesthetic stimulus of natural ‘found’ objects. Surrealism clearly stimulated this interest in the late 1920s, but many architects had collected shells, stones and drift-wood as domestic exhibits for some time. By 1928, Le Corbusier began to collect ‘objets trouvés’ more systematically, for exhibition in his and his clients’ houses and for inclusion in his paintings. His canvas Léa, for example (1930) plays on the erotic implications of a sea shell and a bone, contrasted with the traditional female icon of a violin [15]. We know from sketches he made that these objects were imagined in an open-air setting on a metal table and close to a tree trunk at the vacation house he stayed in on the Bay of Arcachon. Thus, close proximity to nature, natural objects and artistic invention are brought closely together.

But, how could Le Corbusier rescue natural materials from his sworn enemies in the Style Régionaliste? The French art critic Camille Mauclair had attacked Le Corbusier in a series of articles in Le Figaro, in part for putting stone masons and other craftsmen out of work. These honest ‘hommes de tas’ (craftsmen) were threatened by the supposed mechanisation of building which Le Corbusier appeared to favour. Furthermore, clean-cut masonry belonged to the world of the Beaux-Arts architects, who were the natural enemies of Modernism. The answer lies in the notion of ‘objets trouvés’ or ‘objets à réaction poétique’. The avant-garde could recuperate the vernacular only if it was stripped of its nationalist and traditionalist associations and rediscovered as a fragment of ‘nature’. So, instead of dressed stone and decoration designed by architects, Le Corbusier used the modest moellon , a simple, honest, local material, comparable to the pine trunks of the fisherman’s log cabin and assembled by local masons.

The first attempt to use a local builder and ‘natural’ materials, the Villa de Mandrot at Le Pradet (1929-32) had not been easy[16]. The project began in December 1929 as a reutilisation of the Maison Loucheur type house, which used a 45cm stone wall, built locally, to which two prefabricated steel sections were attached. Between March and April 1930, this project was eventually replaced by a scheme which marked the definitive end of the Purist villas. Walls of local stone were interspersed with large steel framed windows manufactured in Paris. Instead of being raised above the ground on pilotis, the house was buried in the ground, with a large terrace on one side. The local maison, signor Aimonetti, did not understand the primitivist aesthetic of the Parisian architects, who refused to allow him to render the stone walls, nor to line the doorways and other opening with brick. In the event, the house leaked badly, from water penetrating the soft local stone and its joints and through the window seals.

Just back from Venice in August 1934, where he had been lecturing on art, Le Corbusier received a letter from Albin Peyron, Commissioner General of the Salvation Army in Paris. Le Corbusier and Peyron had become close friends during the three construction projects for the Salvation Army: the dormitory wing, Cité de Refuge and the houseboat dormitory. Peyron had bought a plot on the road to the beach through the pine forest at Les Mathes, 20 kilometres North of Royan. His sister had already bought a plot there. He had told Le Corbusier at the inauguration of the Cité de Refuge in December 1933 that he wanted to build a summer house, and this was his chance. Peyron sent some photographs of the site and some sketches of his own, which he claimed to be in accordance with Le Corbusier’s manner of thinking. He labelled some of these with the name he had decided for his villa, ‘Le Sextant’ [17].

Il va sans dire que, si dans vos cartons vous avez quelques projets de peites villas répondant aux desiderata suivants: une grande chambre commune, une chambre pour deux filles, une chambre pour un garçon, une chambre pour les parents, une chambre pour deux domestiques, éventuellement une chambre pour amis, et qui me permettent d’apercevoir la mer de la chambre commune, c’est-à-dire à la hauteur des yeux par rapport au sol 3m50 a 4m, je serais très heureux de venir les consulter chez vous [18].

The site (c.32m80 x 34m50 on one side and 44m25 on the other) was on the East side of a road heading almost due south to the beach through pine trees on sandy soil. Peyron’s sketches showed a two storey ‘L’ shaped plan with a belvedere on the third floor.

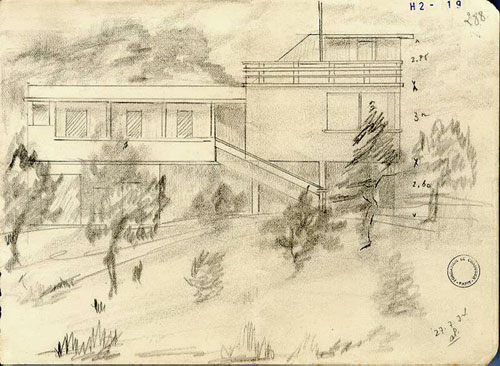

Figure 6 Albin Peyron, sketch of a villa for his site at Les Mathes, dated 27 July 1934 and sent to le Corbusier on 1 August (FLC H2(19)288)_copyright FLC_ADAGP

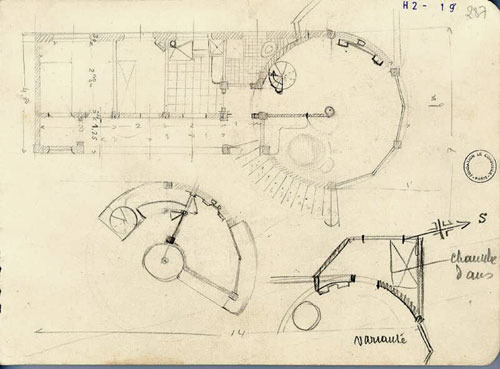

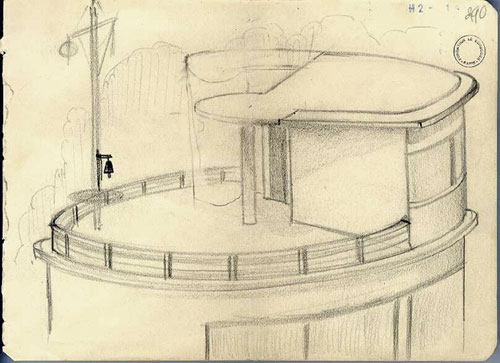

In this perspective sketch, we can assume that the kitchen, servants’ rooms and guest bedroom would have been on the ground floor, with a staircase rising to a balcony with bedrooms for the children and a bathroom. The master bedroom and living room (‘salle commune’) would have been on the right (South side), with a window which in true Modernist fashion ‘turned the corner’ facing the view to the sea. A belvedere on the third floor would have allowed a better view to the sea. In a variant, the salle commune turned into a large circular living room with the master bedroom perhaps on the roof, up the spiral staircase. A guest bedroom would have been attached to the South East. Peyron amused himself by imagining the interior of this living room.

Figure 7 Albin Peyron, sketch plan for a villa at Les Mathes, dated 27 July 1934 (FLC H2(19)287)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

Figure 8 Albin Peyron, sketch of living room in his design of 27 July 1934 (FLC H2(19)289)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

Figure 9 Albin Peyron, Belvedere on top floor of his project for a villa at Les Mathes, probably sent to Le Corbusier on 1 August 1934 (FLC 290)_copyright FLC_ADAGP

A sketch for a belvedere on the top floor may indicate this bedroom (Figure 9).

Le Corbusier replied on 7 August warmly accepting Peyron’s challenge: ‘Je serai, personnellement, très heureux de pouvoir vous loger dans une belle petite maison Le Corbusier’ but suggesting that they talk about this again in September [19]. Peyron then sent a letter and some more sketches of a third and fourth project on 17 October 1934, to try to prompt a response from his friends [20].

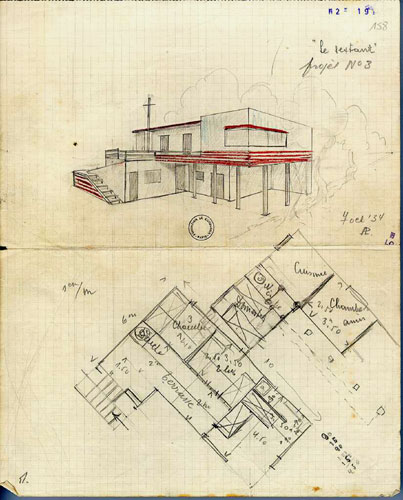

Figure 10 Design by Albin Peyron, dated 7 October 1935, for a third project for his summer house at Le Mathes, sent to Le Corbusier on 17 October (FLC H2(19)158_copyright FLC_ADAGP

The ‘third project’, like several others of these sketches, incorporates an ‘L’ shaped plan, with a ‘salle commune’ for Albin Peyron and his wife and bedrooms for his son and two daughters above a kitchen and bedrooms for two maids and a guest room. A terrace on the first floor would give a view of the sea through the pine trees, while also providing shade below to eat out. An extraordinary ‘fourth project would have aligned the children’s bedrooms, above, and servants’ rooms, kitchen and guest room, below, along the East side, with a double height ‘Salle commune’ all along the West side [21].

On 8 December, Peyron visited Le Corbusier’s atelier in the rue de Sevres and there, judging by his letter of 12 December, he was shown a lightweight prefabricated project, a ‘weekend’ house, which he admired but rejected [22]. The identity of this project is mysterious. Here is Peyron’s description.

“C’est avec la plus grande attention que j’ai étudié depuis samedi votre projet de maison “week-end”. On y retrouve les idées très originales dont vous avez toujours été les instigateurs, et dont je suis un très fervent admirateur. Ce projet répond parfaitement aux desiderata auxquels doit prétendre l’homme désireux de passer un, deux ou quelques jours en un semi-camping au bord dune rivière, d’un lac. La construction légère, la cellule assez réduite, mais qui se continue sur la terrasse ou un terre-plein grâce à son mur basculant, les matériaux légers (bois, éternit, aciers et fers), le tout concourt à un habitat construit pour quelques années à bon marché, et que l’on démolira ou abandonnera quand les réparations importantes se feront sentir par l’usure normale du temps.

Mon programme n’est pas essentiellement le week-end, mais plutôt les vacances, c’est-à-dire maison abandonnée 10 mois l’an, mais où l’on vit deux mois sans arrêt, à une époque où l’on recherche le repos, la santé et le confort également.

Le repos vient des sens, de la vue qui aime à se reposer sur ce qui est beau, simple, naturel, de l’ouïe qui désire un peu de silence après l’appartement tumultueux de Paris, la santé nécessaire de bons sommeils, des bains de soleil au besoin, des siestes à l’abri de la chaleur estivale ; le confort requiert une belle pièce, claire, aérée sans excès. Pour ces raisons ma femme et moi attachons une certaine importance au cachet extérieur car en vacances on vit beaucoup autour de sa maison. Il faut de l’harmonie entre l’habitat et l’environnement, le sable et les bois de pins… Une maison qui se ferme bien l’hiver, et qui résiste à l’embrun salé, aux pluies de l’automne”[23].

And he went on to fear for the heat in the ‘cellules’ of their project, the unfunctionality of the windows and the large movable panels. He suggested that they abandon the ‘weekend’ house idea and design an ‘Ocean’ house, using one of the two local builders.

What could Peyron have been shown when he visited the atelier in December 1934? In fact, Pierre Jeanneret was hard at work on a ‘weekend’ house for Mister Félix, the accountant of Carlos de Beistegui, for whom Le Corbusier had designed a Surrealist apartment overlooking the Champs Elysées (1929-33). The Felix house, often referred to as the ‘petite maison de weekend à La Celle St Cloud’, in the suburbs of Paris, was at an intermediary stage in December 1934. A first set of projects by Pierre Jeanneret was in the process of being altered radically by Le Corbusier. What Peyron could have seen in December 1934 was a little house on a triangular site, made of stone rubble walls alternating with walls of Nevada glass tiles, surmounted by concrete vaults [24].

Figure 11 Pierre Jeanneret, intermediary project for Villa Felix, La Celle St Cloud, December 1934 (FLC 9280)_copyright FLC_ADAGP

The Felix project bears no resemblance to Peyron’s description of what he was shown on 8 December. Much more comparable, surprisingly, was a design produced by Charlotte Perriand with Pierre Jeanneret’s assistance, for a weekend house competition organised by L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui in the autumn of 1934 [25]. This project was for a lightweight demountable steel construction resting on simple stone piers with two rows of rooms facing each other across a sun deck. Large wooden baffles could be hinged out to perform three possible functions. Angled upwards, they allowed ventilation at night while protecting the sleepers, while swung out into a horizontal position they could provide shade on the sun deck. Finally, they could be closed up completely when the visitors were away. The bird’s eye view shows a possible location near a river or lake. There are so many points of contact with Peyron’s description that we must assume that it was this project which he saw. It is possible that Peyron was received in the atelier not by Le Corbusier (although he had placed the date in his diary) but by Pierre Jeanneret [26]. It would certainly have been surprising for Le Corbusier to show a project by Charlotte Perriand, who was not supposed to work on her own schemes in the atelier. Tensions were already developing in the atelier between Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, which were exacerbated by the latter’s close personal relationship with Charlotte Perriand.

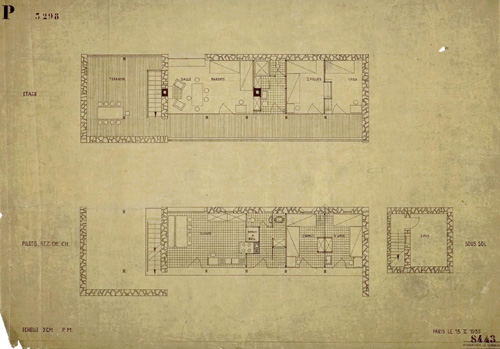

At any rate, by 6 February 1935, a project had been worked up by Pierre Jeanneret for Peyron’s villa. On 19 January Peyron visited Le Corbusier again, and may have been shown some sketches for his villa [27]. A set of drawings were prepared on 6 February which, with various modifications, were submitted to two local masons, William Vallot and H. Béran on 16 February, with an accompanying letter of 14 February [28]. Although Peyron recommended Vallot as ‘plus à la page’, his tender came out slightly higher and Pierre Jeanneret opted for Béran, who turned out to be a conscientious, thoughtful and reliable builder. Le Corbusier, who rarely had a good word to say for the builders of his villas, called him ‘honnête et consciencieux’ [29]. When the house suffered war damage, it was Béran who made the repairs, which seem to have involved replacing the roof and virtually all the structural woodwork. Close inspection can find very little difference from the original details.

The origins of the Villa Le Sextant are not hard to find. The project is closer to Pierre Jeanneret’s range of interests than Le Corbusier’s, and there are very few interventions on the drawings by the master [30]. As an indication of Pierre’s own work at this time, there are a number of projects for houses using stone and wood or steel, some of them in collaboration with Charlotte Perriand.

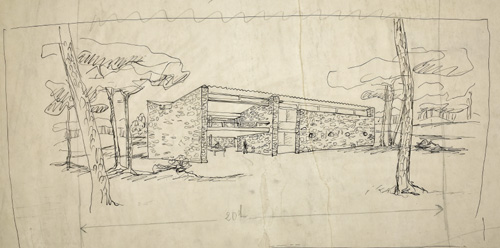

The holiday centre Charlotte designed for a competition launched by L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui in 1935 was submitted with drawings prepared by Pierre Jeanneret and include a number of his favourite themes, including the walls of moellons, the double-pitch roof with a valley gutter and a separate wooden structure inside. Most of the decisive drawings for the Villa Le Sextant are by Pierre Jeanneret, with the assistance of Zunzo Sakakura, Polak, Duntzer and Miquel. The first sketch plan by Pierre, probably dating to mid January 1935, was of a highly compressed house, measuring a mere 14.80m x 5.10m [31]. The minor bedrooms measure a mere 1.90m across, the width of a bed, and the two daughters are accommodated in bunk beds, overlapping at right angles at different heights, as are the servants and guest room beds on the ground floor. In its essentials, this is the house as built, but it is reversed, with the terrace on the right (to the North), rather than the South [32]. There are other significant differences, such as the wall separating the ‘Salle commune’ on the first floor (and the dining room below) from the terrace, which in the first drawings is shown as a wooden partition rather than a stone wall. All the remaining drawings indicate a house of between 17.80 and 19.14 in length, to allow for a little more space in the bedrooms and on the balcony. An important drawing is 08431, where Le Corbusier sketched the house front and back and in bird’s eye view.

Figure 12 Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, preliminary plans and sketches for the villa Le Sextant, mid January 1935. (a) sketches by Le Corbusier of West and East sides of the villa, (b) plan of ground floor, with East side on top (FLC 8431)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

The measured plans indicate the wall to the terrace as a wooden partition, but Le Corbusier’s sketches shows it as a solid masonry wall. The plans are unique in the series in being drawn with the East side on top, instead of the West. A distinctive feature of the plans here are that Pierre has devised large hinged wooden panels, 90cm wide, which could fold away in the summer and close off windows and doors in the winter. These can be seen in an ink perspective of the house published in the Oeuvre complete volume 3 and in Jean Petit’s Le Corbusier lui-même [33]. Like many of the drawings published in the latter book, the original has disappeared into the dealer circuit.

Figure 13 Pierre Jeanneret, perspective of preliminary project for Le Sextant, from SE (reversed in the Oeuvre Complete vol 3 p. 135)_copyright FLC_ADAGP

The full height pivoting panels can clearly be seen in this perspective. As we have seen, Peyron was insistent about the need to close his house off securely during the winter months. In the end, the system for protecting the house was extremely basic, a set of wooden panels cut to the size of the windows, which fit into channels and are held in place by metal studs with a locking key. A number of details associate this perspective with the preliminary designs [34]. The representation of the landscape makes it clear that this is the back of the house and not the front. In the Oeuvre Complète volume 3, and in Le Corbusier lui-même, this perspective view was reversed, to match the orientation of the finished building.

Figure 14 Pierre Jeanneret, perspective of the preliminary project for the house from the North West (street side) before the reversal of the design (FLC 8397)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

The matching perspective, which may also have been shown to Peyron on 19 January, shows the view from the street [35]. This sketch curiously omits the staircase to the upper storey, as well as the wooden post supporting the terrace. This may have prompted Peyron on 3 March to suggest getting rid of the post supporting the balcony (see below).Then, a plan (8444) and two elevation drawings (8391 and 8460) were simply turned over and re-dimensioned and relabelled on the other side in ink, reversing the orientation. There were probably two main reasons for placing the terrace at the South end. Entrance from the road was at the North end and Peyron several times alluded to the need for privacy from passersby on the road to the beach. Furthermore, all his own projects had placed the main living areas and windows to the South and West, with the view to the sea. It is quite possible, therefore, that this change was made after Peyron had seen the first sketches on 19 January. Both versions had turned the bedrooms away from the street, to the East, with a nearly blank wall on the West side.

Figure 15 Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, plans of project of ‘Le Sextant’ (13 February 1935) used for tendering on 14 February 1935. (FLC 8443)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

Peyron was an attentive and critical client. He made detailed comments on the technical description which Pierre had sent the builders on 14 February with the plans, in a letter of 3 March [36]. For example, he criticised the narrow band of concrete outside the bedrooms on the East side, ground floor. He suggested that this should be extended almost to the overhang of the balcony. In the end, only part of this extra screed was laid by Béran, and it was not until the repairs after the war that Peyron’s request was carried out.

Figure 16, View of East side from South with the dining room and kitchen on the ground floor and the ‘salle commune’ on the floor above. The additional strip of concrete screed added by Béran after the war, and the two additional posts can clearly be seen.

copyright Tim Benton

This can clearly be seen today, along with the two additional posts which Béran placed at the outer end of the balcony to stiffen the supports.

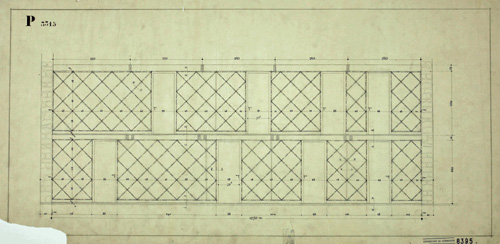

Another feature of the ‘devis descriptif’ which Peyron rejected was an extraordinary system of fenestration on the East side. Pierre described this as: ‘une sorte de treillage en bois dont les mailles auront environ 50cm par 50cm (50×50) posées a 45° et recevant des verres mastiqués a l’intérieur’ [37]. Drawings exist of this system.

Figure 17 Elevation drawing of fixed windows covering the bedrooms on the East side of Le Sextant, drawn by Duentzer, dated 4 March 1935 (FLC 08395)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

These diagonal windows would have been fixed, leaving the ventilation only to the doors. Peyron’s comment was acerbic: ‘Le grillage façade sud-est me parait peu pratique, cher, les carreaux (240) sont difficilement lavables, cassables etc…Prevoir une façade plus simple’. This had immediate effect and no more was seen of this system of ‘mur neutralisant’. It will be remembered that the hermetically sealed window of the Cité de Refuge had created drastic problems of over-heating in the summer. The Salvation Army had to force Le Corbusier to open ventilating windows in the façade with a police order. It seems that here at least, Pierre gave up without a fight. Another point of criticism on the part of Peyron was the wooden post supporting the West terrace, which, as we have seen, Pierre inadvertently left out of the perspective sketches. Peyron suggested that this support could be left out and replaced by a braced truss consisting of two beams forming a balustrade from whch the edge of the terrace should be hung [38]. Pierre wrote in the margin ‘suppression du poteau’, and in a letter of 12 March to Béran he wrote: ‘Sur la grande terrasse de l’étage nous supprimerons le poteau coté sud-ouest et nous le remplacerons par une solive assemblée qui franchira la portée de 5 mètres environ , vu la facilite que nous avons à faire ce genre de construction. À ce sujet, vous recevrez des croquis [39]. In the event, Béran put in the post anyway, admitting that he had not read the revised drawings carefully enough [40]. Even with the wooden post, the terrace has noticeably sagged.

Figure 17 View of terrace on South West side, showing the post supporting the terrace and roof which Béran added against Peyron’s wishes.

copyright Tim Benton

Another point which raised a difficulty was the colour of the stone, which is very white, even today. Peyron and Pierre would have preferred a more mellow colour, and Peyron sent the architects a photograph of a house Béran had built on the other side of the road.

Figure 18 Villa Malatrapp, built by Béran opposite the villa ‘Le Sextant’

copyright Tim Benton

Pierre asked Béran to use the same colour and texture as he had used on this villa. Béran replied saying that unfortunately, he had used recuperated stone which was now unavailable for this house. He recommended the local stone, ‘moellon dur de Saujon’, which he claimed to be resistant to water infiltration and much better than the alternative, pierre de St Palais. Béran insisted on 31 March that half the stone for the house had already been delivered and that no other was available [41]. The white colour of this stone continued to cause anxiety, and Pierre had to reassure Peyron that it would weather to a warmer tone. When Béran offered a compromise, proposing to use some salvaged stone to create a warmer effect at the corners and around the windows and doors, Pierre refused absolutely [42].

It was the builder Béran who insisted that the walls should be 45cm thick and not 40cm as indicated in the drawings. But if Pierre accepted this change, he would not give in to Béran’s practical suggestion to plaster the internal walls [43]. Since Le Corbusier had ‘discovered’ his neighbour’s wall in his penthouse studio at 24 Nungesser et Coli, he had insisted on leaving the bare stone pure, inside and out (Figure 25). In Le Sextant plywood was to be used for the ceilings and partitions, and it was eventually decided to insulate these with cork to control the transmission of sound.

Figure 19 Interior of girl’s bedroom. This would originally have had two beds in it

copyright Tim Benton

Figure 20 Flue in the party wall of Le Corbusier’s penthouse suite studio 1932-3

copyright Tim Benton

A detail which strikes an odd note is the flue of the fireplace in the Salle Commune. Le Corbusier had made a feature of the pink firebricks lining the flue in his studio. Admiring the contrast with the golden stone of the wall.

There are some intriguing drawings, both for ‘Le Sextant’ and for the villa Félix, where a masonry wall and red fireplace flue are celebrated in a coloured rendering, usually with a man standing by it in a manner redolent of ‘homeliness’ [44]. The reintroduction of the warm ‘foyer’ as the heart of the Corbusian home was a new invention of the 1930s and, in my opinion, owes a great deal to the influence of Pierre Jeanneret, since these emblematic drawings are in his hand.

Figure 21 Pierre Jeanneret, drawing of the hearth in the ‘salle commune’, showing arrangement of firebricks inserted into the stone wall (FLC 8409)

copyright FLC_ADAGP

Figure 22 ‘Le Sextant’ ‘Salle commune’ with fireplace

copyright Tim Benton

Figure 23 Terrace, showing the flue of the fireplace in the ‘salle commune’

copyright Tim Benton

Béran has not understood the informal effect which Le Corbusier and Pierre wanted with this detail. He has organised the firebricks in a symmetrical, hard-edged structure, like a corss of Lorraine. The view of the terrace (Figure 29) also shows the blue painted panels (n the right), used to cover up the windows in the winter months. These slot into grooves in the window frames and are held in place with steel studs and a metal key. The twin beams gripping the posts which rise right up to support the roof can also be seen, as well as the Eternit panels closing off the lower half of the window walls. Originally, none of the windows were meant to be openable, but an opening window in the kitchen, at the end, was introduced for ventilation.

Figure 24 View of window wall of bedrooms on the ground floor, East side, showing the Eternit panels-copyright Tim Benton

The wooden details in ‘Le Sextant’ are intriguing because they suggest a Japanese influence which makes sense when you realise the interest of Junzo Sakakura in the project. He drew many of the presentation drawings and may have suggested many of the wooden details in the house.

Figure 25 Detail of twinned beams on the balconies

copyright Tim Benton

Figure 26 Detail of staircase showing hand rails probably designed by Sakakura

copyright Tim Benton

The villa ‘Le Sextant’ owes a great deal to its client, Albin Peyron and to the interest of both Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in the vernacular. Their approach was a staunchly modernist one. Natural materials had to be used in a ‘pure’ form, even if this meant ignoring much local wisdom about sound construction. The builder Béran managed to persuade them to avoid some of the pitfalls, stiffening the roof structure against the wind, ensuring reasonable insulation (Pierre wanted to use wood shavings between the plywood panels) and protection from water penetration. Le Corbusier and Pierre showed, in this project, how to adapt the fundamental principled of the Modern Movement to new materials, sites and circumstances.

[1]- The villa was published in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, No 9, September 1935, p. 65 and discussed in Ragot, G. and M. Dion (1997) Le Corbusier en France. Paris, Le Moniteur, p. 205-7

[2]-{Le Corbusier, 1964 #17329}, p. 138.

[3]Brooks, H. A. (1997), Le Corbusier’s formative years : Charles-Edouard Jeanneret at La Chaux-de-Fonds, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, p.5 and 185-190.

[4]Passanti, F. (1997), ‘The vernacular, Modernism and le Corbusier’.’ JSAH, 56:4, December 1997, pp. 438-45

[5]Reichlin, Bruno, ‘Cette belle Pierre de provence’ La villa de Mandrot’, Le Corbusier et la Meditarrenée, Marseilles, 1987, pp. 131-140

[6]Le Corbusier (1989), Une maison, un palais, Paris, Editions Connivences, pp.48-52

[7]Loos, Adolf, ‘Architecture’ in {Loos, 2002 #13520}, pp. 73-85

[8]Le Corbusier, Une Maison un Palais, Paris, 1928, p. 46

[9]The original sketches are in Le Corbusier Sketchbook¸ I, B6, pp. 389 and 390 (redrawn later and included in La Ville Radieuse The Radiant City, (Le Corbusier (1967), The radiant city; elements of a doctrine of urbanism to be used as the basis of our machine-age civilization, New York, Orion Press, p.29.

[10]Le Corbusier (1967), The radiant city; elements of a doctrine of urbanism to be used as the basis of our machine-age civilization, New York, Orion Press, pp. 53-5

[11]Le Corbusier (1967), The radiant city; elements of a doctrine of urbanism to be used as the basis of our machine-age civilization, New York, Orion Press, p.53

[12]In addition to Le Corbusier and his friends, André Lurçat and the Italian modernists looked to the white-painted vernacular of the Mediterranean, while German architects valued the half-timbered barns and collective houses of their regions.

[13]Christopher Green, ‘The architect as artist’, in Le Corbusier Architect of the Century, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1987, pp. 110-157.

[14]{Barsac, 2005 #5626}, p. 146

[15]{Green, 1987 #10580}, pp. 115-6

[16]{Benton, 1984 #1486}

[17]For example, his sketch of ‘projet no 3’ (FLC H2(19)158)

[18]Albin Peyron to Le Corbusier, FLC H2(19)154

[19]H2(19)156

[20]H2(19)157

[21]H2(19)159 and 160.

[22]H2(19)161

[23]Albin Peyron to Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, 12 December 1934 (FLC H2(19)161)

[24]For a detailed history of the Félix house see {Benton, 2001 #10080}, also in {Benton, #1496}. A plan closely related to FLC 9280, but without the top storey (FLC 9275), was dated 17 December 1934

[25]See {Barsac, 2005 #5626} p. 152-3 and {Benton, 2005 #11922}p. 21-2

[26]The diary entry for 8 December reads ‘Samedi 3h Peyron bureau’ (FLC F3(5)9 p. 51).

[27]The diary entry reads simply ‘3 ½ Peyron’ (FLC F3(5)9 p. 59).

[28]FLC H2(19)179, 191, 239. Vallot’s estimate came out at 79,183 frs, while Béran’s was a round 60,000 frs (FLC H2(19)183 and 192.

[29]{Le Corbusier, 1964 #17329}, p. 135

[30]One of the few sketches in his hand are the perspective views of the house in its preliminary form, reversed with respect to the project of 6 February 1935 (FLC 08431).

[31]FLC 08429

[32]The North point on FLC 8425 and other plans, as well as various perspectives, makes clear that all these plans are drawn with the West facade, facing the road, on top and the North to the right.

[33]{Le Corbusier, 1964 #17329}, p.135 and {Petit, 1970 #11499}, p. 81.

[34]For example, the staircase is reversed, the waterspout and the balcony balustrade were detailed differently in all the subsequent designs.

[35]FLC 08397.

[36]H2(19)238

[37]H2(19)239

[38]Two drawings show these trusses (FLC 08413 and 08432).

[39]H2(19)201

[40]Béran to Pierre 19 June 1935 (H2(19)234

[41]H2(19)203

[42]Pierre Jeanneret to Béran, 20 March 1935 (FLC H2(19)206).

[43]Béran to Pierre Jeanneret, 15 March 1935 (FLC H2(19)203).

[44]FLC 9270

Bibliography

Barsac, J. (2005) Charlotte Perriand : un art d’habiter, 1903-1959. Paris, NORMA

Benton, T. (2003) ‘The petite maison de weekend and the Parisian suburbs’. Le Corbusier and the architecture of reinvention. M. Mostafavi. London, AA Publishing: 118-139

Benton, T. (Oct, Nov, Dec 1984) ‘La villa Mandrot i el lloc de la imaginacio’ Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme 163: 36-47

Benton, T. ‘La maison de weekend dans la banlieue parisienne’ IX Rencontre de la Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris, 2001

Benton, T. (2005) ‘Charlotte Perriand: Les années Le Corbusier’. Charlotte Perriand. Paris, Editions du Centre Pompidou: 11-24

Green, C. (1987) ‘The architect as artist’. Le Corbusier architect of the century. London, Arts Council of Great Britain: 110-130

Le Corbusier and P. Jeanneret (1964) Oeuvre complète 1934-1938. Zurich, Les Editions d’Architecture [Editions H. Girsberger, Edited Max Bill, 1938]

Loos, A., A. Opel, et al. (2002) On architecture. Riverside, Calif., Ariadne Press

Petit, J. (1970) Le Corbusier lui-meme, Paris

An Italian translation (curated by Andrea Canziani) of this text is published in “Le Case per artisti sull’Isola Comacina”, Andrea Canziani, Stefano Della Torre (a cura di), Quaderni Fondazione Montandon n.7, Nodo Libri, Como 2010

Thanks to Mr. Michel Richard/Director of Le Corbusier Foundation_Paris