Hans Ulrich Obrist intervista Cedric Price

Hans Ulrich Obrist

In the context of Cities on the Move, I think one of the reasons your work has been so important to many architects in Asia has a lot to do with the notion of time and the ephemeral, something which is understood better in Asia than in Europe.

Cedric Price

A short lifespan for a building is not seen as anything very strange in Asia. Angkor Wat in Cambodia is so vast and yet it lasted for less than three hundred years. I liked your dependence on change in the Cities on the Move exhibition and I particularly liked the Bangkok exhibition where time was the key element. I see time as the fourth dimension, alongside height, breadth and length. The actual consuming of ideas and images exists in time, so the value of doing the show betrayed an immediacy, an awareness of time that does not exist in somewhere like London or indeed Manhattan. A city that does not change and reinvent itself is a dead city. But I do not know if we should use the word ‘city’ any more; I think it is a questionable term.

HUO

What could replace it?

CP

Perhaps a word associated with the human awareness of time, turned into a noun, which relates to space.

HUO

The paradox is that the city changes all the time, so it would have to be a word in permanent mutation; it could not be a frozen term. But let’s return to the idea of dead cities, tell me more about why they die?

CP

Cities exist for citizens, and if they do not work for citizens, they die.

HUO

Which is interesting because you also talk about the fact that buildings can die.

CP

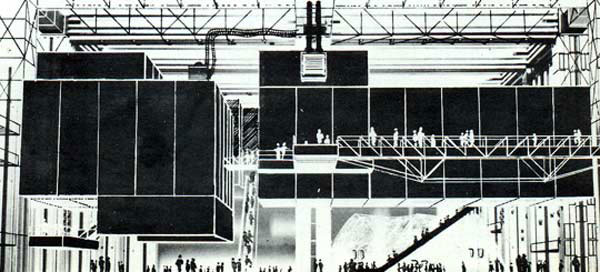

Yes, the Fun Palace was not planned to last more than ten years. The short life expectancy of the project had an effect on the costs, but not in a limiting, adverse way. No-one, including the designers, wanted to spend more money to make it last for fifty years and we had to persuade the generators and operators to be economic in terms of both time and money. The advantage, however, was that the owners, the producers and the operators, through necessity, began to think along the same lines, as the project created the same set of priorities for everyone. That should be one of architecture’s aims; it must create new appetites, rather than solve problems. Architecture is too slow to solve problems.

I suppose we should ask what is the purpose of architecture? It used to be a way of imposing order or establishing a belief, which is the purpose of religion to some extent. Architecture does not need that mental imperialism any more. As an architect, I do not want to be involved in creating law and order through fear and misery. I see the creation of a continuous dialogue as both interesting and also perhaps the only reason for architecture. In the sixteenth or seventeenth century, someone defined architecture as ‘commodity, firmness and delight’. Commodity equates to good housekeeping, particularly in terms of money; firmness is the structure; and the delight factor is the dialogue.

HUO

On that subject of dialogue, let’s return to the Cities on the Move show in Bangkok. Due to the open structure and the lack of contemporary art museum in Bangkok, the city entered the museum and the contents of the show were carried into the city. The museum opened to the world.

CP

That’s it – museum world, world museum. The exhibition in Bangkok was all about dialogue; it acted as a key for the people who experienced the show, only to realise that they were experiencing it all the time. It was the same with the Fun Palace; it was never intended as a Mecca - a lovely alternative to the horror of living in London – but instead it served as a launch pad to help people realise how marvellous life is. After visiting the Fun Palace, they went home thankful that their wife looked as she did and that their children were noisy; the ‘key’ had opened the door for them. The Fun Palace was a launch pad to reality, mixed with a large portion of delight.

However, I think that, at present, architecture does not do enough; it does not enrich or enliven people’s lives as much as, say, the internet, or a good story, or music, does. Architecture is a poor performer; even the Magnet City schemes never happened. As an architect, I am trying to make architecture a better performer. With human beings answering questionnaires and me reading the answers, I hope to recognise opportunities for improving the human lot by architecture.

HUO

Alexander Dorner, the great hero of museums of change who ran the Hanover museum in the early twentieth century, wrote that institutions should be like dynamic power plants. Could you tell me about your museum-related projects, which address the concept of the portable or ephemeral museum.

CP

When the Queen Elizabeth was up for sale, I suggested a museum in the ship, so that you could travel like a millionaire while the ship stayed in the bay in Liverpool; it was at sea but only a short boat ride away. The Atlantic crossing which used to take four or five days was concentrated into eight hours, the time you could take to go around the ship. You could see the machine rooms, the kitchens, the lavatories, the tennis courts and all the paraphernalia of the ship, but primarily the luxury of it. The ship was on hydraulic jacks and a range of seasonal crossings, relating to the weather you would have experienced in the Atlantic, were on offer. You would then realise why, in rough weather for example, the tables were made with edges on them to prevent the plates from slipping off.

I also did a scheme for the Tate, which they did not select. It turned the power station into an object. I proposed building a glass box over the whole thing, so that the business of producing exhibitions would have become secondary to the main exhibit, which was in a box with a single door. In bad weather, it would have been like one of those snowstorms, with Jesus being the one to shake up the snow! I was assuming that it could last at least a year or so, and then they could decide what kind of object they would put in the Tate.

HUO

So it was like a Russian doll, since the exhibition would have been an exhibition within an exhibition.

CP

Yes, that is right.

HUO

There is an interesting and productive paradox between, on the one hand, your projects for temporary buildings and dynamic institutions, which would eventually auto-dissolve and, on the other, your interest in old museums.

CP

I think that the notion of the classic museum still has – limited – viability. At three o’clock every afternoon, I get very tired. I am no use in the office so I go to this wonderful distorter of time and place called the British Museum. It distorts the climate because the building has a roof over it; it distorts my laziness, because I do not have to go to Egypt to see the pyramids; and it distorts time, because I can see someone wearing an Elizabethan dress. The distortion of time and place, along with convenience and delight, opens up a dialogue that reminds people how much freedom they have for the second half of their life.

This automatic distortion, whether of time or of place, when you visit a museum is a good thing. If you visit the same museum on two consecutive wet Thursdays, it will be different on both occasions. You will have distorted the contents of the museum through familiarity, which only occurs through going twice, rather than once. The distortion then becomes two-fold. There is the compaction of old bits of history into a convenient time and place for the consumer and then there is the added distortion of going there today with you, which was quite different from going there alone.

HUO

We both looked at it differently than we would have done, had we been on our own.

CP

Yes, but the distortion was also that we were both in London, which is not our home. It is about the enrichment and enlivenment of a new time dimension, or a new pace of events, which differs from the normal passing of time.

Museums, far more than art galleries, have to distort time, otherwise the element of coincidence in the collection does not occur - the distortion of time between when the objects were created and when they are shown. There is a quality to museums which is more relevant to the present time and to seeing the objects in the museum than to the date of their creation.

HUO

Some people stay longer than others when they visit museums.

CP

Yes and it does not matter whether a lot or a little is seen. A person who gets bored after five minutes in the museum can enjoy just as much as the person who stays for an hour. Museums are not only about a distortion of time, but also a distortion of the quantitative quality of content.

HUO

You mentioned a survey that the Tate carried out of their visitors.

CP

Yes, they discovered that most of the people they observed spent between five seconds and one minute reading texts about the work and from two to fifteen seconds looking at the work itself!

HUO

This fact influenced your project at CCA in Toronto, called Mean Time. Could you tell me about the exhibition?

CP

Yes, I created a series of symbols which were shorthand – or graphic reminders - for the points I wanted to make about the exhibits. They were displayed like postage stamps against the works. The actual printed catalogue explaining the exhibits was only available when you picked up your coat from the cloakroom, just before leaving. Until then, you had to use the symbols and look at the objects.

HUO

Do you see other ways of using labels to prevent the museum visit from becoming a frozen experience?

CP

In museums, the labels to the objects carry dates, which is not necessarily the case in an art gallery. Imagine that somehow you could make these dates - a thousand years BC, unknown, 2000 - vanish and then reappear. It is not beyond the possibility of electronics today; a certain switch could be turned on and the dates on the labels would be made visible again.

HUO

That is a lovely idea! Things would appear and disappear.

CP

It has nothing to do with distortion, but is about the announcement of information that you can be, or want to be, fed.

HUO

This leads us to the question of density or non-neutrality. How do you feel about the omnipresent ideology of the white cube?

CP

Obviously it is nonsense. A museum or gallery cannot be a neutral space, because the degree of distortion ensures that it never will be. Why would all the objects be together? This so-called neutral space that people want cannot exist, because of all the coincidences caused by the personal objects.

HUO

Rather than the awkward model of the white cube, I would prefer to explore your ideas about the urgent need for museums as places of transitional dialogue and cultural production. Could you talk a bit about your time-based project in Glasgow and how that opened up a dialogue between the city and its citizens.

CP

The city hall is in the centre of Glasgow. They are very proud of it and people are not allowed in very often, unless they have got a complaint against the city. We decided to improve the lift to the top of the tower – putting a carpet in, installing lovely mirrors, spraying it with perfume - and invited the public in. We did not tell them why; all we said is that they could go to the top of the tower and for free. In the lift was a tape announcing ‘Tonight, all the areas which we think should be saved without question will be floodlighted red.’ Only parts of the city were lit up, so their attention was focused. You heard comments like: ‘Well of course that church should be saved’ and ‘Why keep that slum?’ The next night, different areas of the city were flooded green, indicating districts they decided should be improved. On the last day, the floodlights were white. The public was invited to tell the city what they should do with the spaces lit in white. There were no ’superiors’ involved, no architects with patches on their tweed jackets around for miles. The city was saying, ‘We’ve thought about it for years and still don’t know what to do with the white areas. You tell us. But don’t tell us next year, tell us within a month, because after that it’s too late. As you go down, pick up a free postcard and mail us your response.’

HUO

Can you give me an example of an institution, other than a museum, where you feel that the boundaries of discipline and time have successfully been transgressed?

CP

The AA (Architectural Association) used to be a good example. Geoffrey Bawa and I were at the AA together. It was a rare thing because the AA had people of different ages, and not just different nationalities. For instance, there was an architect from India who already had an office of about forty employees, and this was is in the 1950s in India. He came to do five years at the AA and encouraged younger people. Peter Smithson once gave a lecture about the advantages of architectural cribbing and, although it was years later, Geoffrey Bawa and this Indian architect were perfect examples of that. They were only too pleased to show other people what they were doing or to help them. Smithson was saying that cribbing is valuable, but he was not talking about the kind of generosity that Bawa and this Indian man showed about what they knew. They were helping people who were younger than them and were not worried about their schemes being cribbed; they were above that. At that time, the AA was both trans-disciplinary and trans-generational.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a Swiss curator and art critic. He presently serves as the Co-Director, Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery

Cedric Price, architect, is died in 2003

© The authors, 2001