Joel Sternfeld_Experimental Utopia in America

Arcadia Cohousing, Carrboro, North Carolina, April 2005

The home of Giles Blunden is independent of the public power grid. The solar panels visible on his roof provide electricity and heat water. Blunden is the chief architect and founder of Arcadia Homes, a sustainable cohousing community in which all thirty-three residences have passive solar design (non-mechanical solar heating achieved through site selection and large south-facing windows) and some active solar elements (collecting the sun’s rays by appropriate technology to provide heat, mechanical power or electricity).

In addition to its solar features, Arcadia is a pedestrian-friendly community that preserved nine acres of climax hardwood forest when it was built, by clustering houses on land covered with secondary- growth pine trees. The distinctive architecture of the community derives from vernacular local millhouse structures.

In 2003 the share of all electricity produced by solar cell technology in the US was 0.07 percent—though as far back as 1979 President Jimmy Carter announced (at a press conference held on the White House roof) the goal of bringing sun, wind and other renewable resources-generated electricity to twenty percent of the US total by the year 2000. In contrast, Japan, where fossil fuels are much more expensive, generated four times the amount of solar electricity produced in the US.

As solar power approaches a cost of $2 per watt, it is becoming less expensive than commercial power. Thirty-eight states, including North Carolina, have enacted “net metering” laws that require utilities to connect residential solar panels into the grid and to compensate homeowners for any excess electricity they produce.

Alpha Farm, Deadwood, Oregon, August 2004

In 1971, four Philadelphians felt a need to change their lives. Instead of directly engaging in social and political activism they decided to, in their own words, “live ourselves into the future we seek.” Together with other urban exiles, they bought 280 acres in the Coastal Range of Oregon. On the property they found an old post office and took its name for their own: Alpha (the first letter of the Greek alphabet, alpha means “the beginning”).

Over the years, there have been thirty-five members (the community’s highest form of affiliation), nine of whom remain at Alpha today. Fifteen to twenty adults and children normally reside at the farm. They earn their collective living farming, doing rural mail delivery, through a cafe-bookstore (the Alpha Bit), and with a consulting practice that offers training in consensus formation.

All decisions at Alpha are made by consensus, a 350-year-old process established by the Quakers. It is based on the belief that each person has some part of the truth and no one has all of it. It is also based on the assumption that everyone is trustworthy (in Quaker consensus, a single person can block a decision if they believe it will cause harm). So the group must work to achieve unity: everyone must agree with the essence of a decision and then support it.

After twenty-five years of attending meetings, Caroline Estes, one of Alpha’s original members, accumulated such wide experience in consensus-based decision-making that her skills as a teacher and meeting facilitator have been in demand by organizations as diverse as Hewlett-Packard and the National Green Party.

After the dissolution of his marriage, Jesse Johnson and his young son Gabriel biked 520 miles down the Oregon coast to join Alpha Farm. Also in the picture: Chaos, the cat.

Ruins of Drop City, Trinidad, Colorado, August 1995

Three of the original founders of Drop City met as art students in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1961. They referred to their practice of painting rocks and dropping them from a loft window onto the busy street below as “Drop Art.”

By 1965 the founders’ desire to live rent free and create art without the distraction of employment led them to a six acre goat pasture outside Trinidad, Colorado, which they purchased for $450. Naming their community after their gravity-driven art was the easy part; building it a little harder. But having recently attended a lecture by Buckminster

Fuller and now joined by a would-be dome builder from Albuquerque, they began with scrap materials and visionary optimism. Sheet metal was stripped off car roofs (for which they paid a nickel or a dime) and attached to the grid of a dome. These building materials not only provided shelter, but they also emblemized the group’s refusal to participate in consumerist society. Money, clothing and cars were shared, and they lived as quasi-dumpster divers.

Initially the community flourished. With a core group of twelve, it functioned as the founders had intended, a hotbed of art- making. But a steady flow of publicity in underground and mainstream media, encouraged by resident Peter Rabbit, led to a torrent of guests. It has been reported that Bob Dylan, Timothy Leary and Jim Morrison visited, but the historian’s chestnut, the primary account, may be less than reliable when it comes to the 1960s. By the time the community decided to abandon its open-door policy, it was too late: the founding members had left, and conditions had taken hold that would bring about a final dissolution in 1973. In 1978 the site was sold; proceeds helped rent space in New York City for exhibitions of the group’s work and to publish it in Crisscross magazine.

The domes sat on the land of A. Blasi and Sons Trucking Company until recently, when they succumbed to gravity.

Dacha/Staff Building, Gesundheit! Institute, Hillsboro, West Virginia, April 2004

When Dr. Patch Adams envisions the forty-bed rural community health care facility that he refers to as “the free silly hospital,” he hopes it will be “funny looking, full of surprises and magic.”

Adams’ desire to humanize healthcare has always taken radical form. From 1971 to 1983, he and nineteen other adults and their children moved into a six-bedroom home and called themselves a hospital. Three of the adults were physicians. They were continuously open to patients and saw fifteen thousand people over a period of twelve years. Initial doctor/patient interviews were three to four hours long, “so that we could fall in love with each other.” Since no donations were received, nor was there any outside funding, the staff eventually left and the hospital closed.

This led Adams to his present period of fundraising, which he often does in the guise of a clown. A three-hundred-acre farm has been purchased in West Virginia—chosen because it is the most medically under-served state in the nation— and two buildings have been constructed. The Dacha/Staff Building was designed by the Yestermorrow Design/Build School of Warren, Vermont.

Amongst numerous other unconventional practices, the hospital will not charge for its services and neither will it carry malpractice insurance. Healing arts such as acupuncture, massage, yoga, herbalism and faith healing will be integrated into patient care. Patients and staff will stay at the hospital, and forty beds will be available for “plumbers, string quartets and anyone wanting a service-oriented vacation,” reflecting Adams’ vision that the health of the individual cannot be separated from the health of the community. Although the free silly hospital is not yet built, the idea of it can and does influence the dialogue on health care delivery systems.

Paolo Soleri at Arcosanti, Cordes Junction, Arizona, August 2000

Throughout the twentieth century, architects have been particularly ready to offer their visions of an idealized urban future. For Le Corbusier, a “Radiant City” would be appropriate to the machine age, providing a highly efficient and organized grid to facilitate modern life. For Frank Lloyd Wright, it was critical that everyone have their own patch of earth on which to realize their individuality: thus his “Broadacre City” not only necessitated personal land to live on, but a car to get there. The Italian-born architect Paolo Soleri is far less well-known to the public than Le Corbusier or Wright, but in the Arizona desert he is quietly building what is perhaps the world’s only true prototype of a futurist city.

Arcosanti is an “Arcology,” a word used by Soleri to describe the harmonious marriage of architecture and ecology. Unlike Wright, with whom he studied, Soleri believes that it is the physical dispersal in the landscape permitted by the automobile that has led to moral and spiritual dispersal in society. By contrast, Arcosanti, planned for five thousand inhabitants, will occupy only two percent of the land normally taken up by a suburban development. Residents work no more than a ten-minute walk from their homes, eliminating the need for cars within the city—consistent with Soleri’s prophecy of the eventual extinction of the automobile. Reminiscent of the historic center of Italian cities, every aspect of Arcosanti’s design, including numerous balconies, terraces and piazzas, encourages a maximum of social interaction. Soleri is also critical of excessive consumption of resources. To avoid wasting materials, gardens, solar heating and natural cooling move the community toward self-sufficiency.

Arcosanti has been under construction for thirty-five years, self-funded by the sale of distinctive wind chimes and bells that are forged on site. It is being built by students and volunteers—progress is at once achingly slow and surprisingly fast. Visitors will find a substantial and unusual small community of about fifty permanent residents, and significant glimpses of a city that feels ancient and futuristic as it rises.

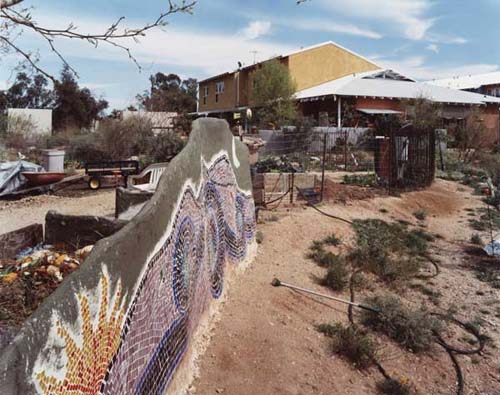

Sonora Cohousing, Tucson, Arizona, March 2005

In many ways Sonora Cohousing is typical of all cohousing—numerous environmentally sound practices are woven into the thirty-six homes and throughout the 4.7 acre site. Townhouses sit in groupings of three or four units around highly landscaped “placitas,” forming natural conversation points in the landscape. The “green-built” homes are energy efficient, with active and passive solar energy elements and are structured to facilitate water harvesting. The community’s three thousand five hundred square-foot common house is built from straw bale. Sonora’s social practices are also typical of cohousing: community, collaboration, conservation. But the most unusual aspect of the community is no longer visible to the eye: Sonora cohousing is intentionally built on an urban infill site.

“Infill development” refers to the practice of making use of underutilized or empty sites within urban areas. The founding members of Sonora wanted to avoid destroying untouched desert—“blading unbladed land”— or becoming part of the suburban sprawl that requires new roads, sewers and schools every time a developer “leapfrogs” to build a community further out from the city center (developers are motivated to do so because the farther land may be less expensive—and offer better “access to nature”). The founders of Sonora not only made a choice for infill, they also adhered to the criteria that the site must be accessible by public transportation (in this case bus transportation) and that shopping must be within walking distance. What’s more, they chose a neighborhood with a high crime rate by Tucson standards, and yet they refused to become a gated community. This has meant that bicycles, and charcoal grills and watermelons, are occasionally stolen—but it also allows for meaningful interactions with neighbors (the three nine-year-old girls who stole the watermelon came back and sought out its grower to apologize).

Surreal Estates, Sacramento, California, July 2005

Surreal Estates is a community of eleven homes and studios being built in North Sacramento by artists for artists. The project has been in the making for eleven years as the artists have sought a site, obtained financing and government approvals, and have planned and designed their homes. Ground was broken on the 1.3-acre site in March 2005, and occupancy was expected before Christmas of that year. The homes will sell for $125,000 to $220,000, depending on the buyer’s income. The prices for these twelve-hundred square-foot homes and eight-hundred squarefoot studios are considerably lower than current Sacramento prices, because the artists and their families and friends are doing virtually all of the work. Each artist is required to put in at least thirty-five hours a week on the job, but many are logging closer to sixty, despite summer temperatures that often reach a hundred degrees in California’s Central Valley—giving new meaning to the term “sweat equity.” Motivating the artists is their agreement that no one will get a key to a house until everyone can get one.

The $2.4 million project has received substantial loans from local government. As part of the land purchase agreement with the North Sacramento School District the artists have made a commitment to spend one day a week teaching at a local school and to host periodic open studios.

The area in which they have chosen to realize their dreams is a low-income residential neighborhood that has attracted artists and galleries despite a serious crime problem. In 1999 Kyle Billing, a twenty-three-year-old graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, was shot and killed as he loaded supplies into his new studio in the middle of a November day.

The developer for Surreal Estates is Mercy Housing, founded in 1981 by the Sisters of Mercy in Omaha, Nebraska, a group of nuns who specialize in building affordable housing and healthy communities. In analyzing the variability of artists’ incomes, Mercy Housing found them to bear some similarity to those of migrant farm workers.

Lake Tuendae, Zzyzx Springs, California, March 2005

Curtis Howe “Doc” Springer called himself a physician and a Methodist minister, although he was neither. He created the name “Zzyzx” for the health resort he built in the Mojave Desert, hoping it would be the “last word” in resorts. Zzyzx was a Christian resort predicated upon a belief in the curative powers of its mineral waters—and the destructiveness of alcohol and arguing. Smoking, however, was acceptable everywhere but the dining room, bathhouse, sundeck and pool area (the prohibition in these areas related to concerns about the hazard of combining bare feet and burning cigarette butts).

The project began in 1944 when Springer filed a mining claim on an area of land eight miles long by three miles wide on the site of Hancock’s Redoubt, an 1860 army outpost. Using laborers from skid row in Los Angeles, whom he paid with food and showers, he built a hotel on the street he called the Boulevard of Dreams, an airport (Zyport), and a health spa that included a cross-shaped pool and a mechanical exercise horse that had been in the White House during the presidency of Calvin Coolidge.

Zzyzx also had a radio station from which Doc Springer’s nightly broadcasts were beamed to 221 radio stations in the US and 102 abroad. On the air Springer played religious music, preached his folksy religious philosophy, and sold his quack curative products: Hollywood Pep Tonic; Antediluvian Desert Tea, a peppermint herb brew; Zy-Pac, mineral salts from the bed of Lake Tuendae, which users were directed to rub on the scalp, then bend over and hold their breath as long as possible; and Mo-Hair, a purported baldness cure.

It was Mo-Hair that particularly incurred the ire of the American Medical Association and was instrumental in Springer’s 1969 arrest and sixty-day jail sentence. At the same time, the IRS, the FDA and the Bureau of Land Management began legal proceedings against him.

In 1974, Springer and a few hundred of his followers were ejected from Zzyzx, despite his willingness to pay the government $34,187 owed in back rent. He died in Las Vegas in 1986 at the age of ninety. Zzyzx is now referred to by its earliest name, Soda Springs, and is used as the Desert Studies Center of the California State University system. Lake Tuendae has been discovered to be the home of a tiny endangered fish, the Mojave Tui Chub.

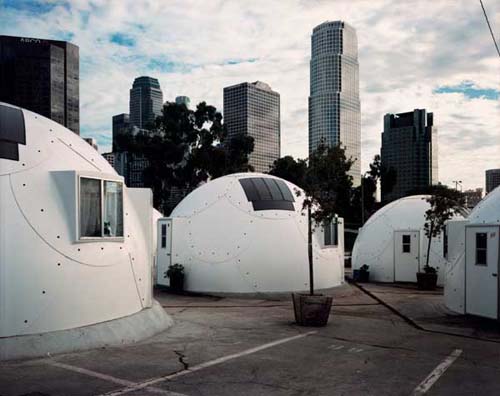

Dome Village, Los Angeles, California, August 1994

This community of experimental fiberglass domes offers transitional housing for as many as thirty-four homeless people. Eight of the domes contain common facilities, including kitchens, bathrooms, laundries and computer rooms. The other twelve provide shelter for single individuals or families.

Activist Ted Hayes founded the village in 1993 as alternative for the many homeless people who are afraid of shelters. The domes allow greater privacy for the people who stay in them, and the village itself acts as a microcosm of society, providing residents with a setting in which they may stabilize their lives and garner the skills necessary to reenter the “real world.”

With their distinctive design, the domes are meant to call the attention of passing motorists on the nearby Harbor Freeway to the problem of homelessness. Initial funding for Dome Village was provided by the Atlantic Richfield Oil Company.

Ted Hayes has a long history of promoting innovative ways to help the homeless that incorporate problem-solving and individual responsibility. He is sometimes referred to as the “Rasta Republican.” In the 1980s he started a cricket team made up of Latino teenagers and homeless men, “Homies and Popz.” The team has played at Windsor Castle and is the subject of a forty-minute operetta commissioned by the Los Angeles Opera.

Milagro Cohousing, Tucson, Arizona, March 2005

Milagro means “miracle” in Spanish. Like the hundred or so other cohousing communities created in the United States in the past fifteen years, Milagro is composed of individual homeowners who are consciously committed to living in community and in accord with ecologically sound principles.

Of Milagro’s forty-three acres, only eight are used for houses. (Part of the “miracle” is the variance from local zoning regulations that it received. Normally, a maximum of one home per three acres is permitted in this part of Tucson. Suburban or outlying communities frequently employ such provisions as a means of maintaining their rural character.) The remaining thirty-five undeveloped acres of Milagro have gone into a conservation easement, open to the public as a nature reserve and protected from development.

Milagro’s commitment to being in balance with nature is particularly manifest in its water harvesting methods. Believing that this resource will become increasingly scarce, all water that exits the community’s homes, including “grey water” that has been used for cooking and bathing, is recycled through a wetlands system and eventually returned to be used to irrigate plantings. Every structure is built with a steep roof, allowing rainwater to be directed through gutters and funneled down water spouts into cisterns, in an active water-harvesting system. Earthen basins and berms and the extensive use of native plants slow down and hold rainwater, so that it doesn’t run off before plants have absorbed it.

The World Water Forum has predicted that sixty-six countries containing two-thirds of the world’s population will experience moderate to severe water scarcity by 2050. Whether the global water crisis is yet to come or is already present remains subject to debate, but evidence of global environmental problems continues to accumulate rapidly. In the year 2000, according to the International Red Cross, more of the world’s millions of refugees had fled their home places for environmental reasons than because of war.

Community Center, Mason’s Bend, Alabama, April 2005

In 1991, Samuel Mockbee set aside his successful architectural practice and moved to Alabama to join the faculty of Auburn University. In the course of his work, Mockbee, a fifth generation Mississippian, had observed the deep social and economic inconsistencies of life in the South, and he was anxious to do something in response. With this sense of mission, he and D.K. Rath, an architecture professor and long-time friend, founded the Rural Studio—essentially an architectural practice for the impoverished, in which students and teachers live in the rural South and build for, and with, their clients. Homes, churches and community centers are constructed to meet real needs and, at the same time, the highest standards of architectural theory and aesthetics. To make this feasible, most building materials are donated or found. Hale County, Alabama, the place chosen for this experiment, has its own symbolic meaning: Walker Evans and James Agee documented it in the 1930s, in what would become the American classic, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

The Rural Studio has built more than nine residences and twenty community projects. Typical of them is the Mason’s Bend Community Center, whose glazed wall is made from the windows of Chevy Caprice Classics—purchased from a junkyard in Chicago on an “all you can carry out for a buck” day.

Other notable projects include the Lucy House, made from seventy-two thousand recycled carpet tiles; the Shiles House, built in a wet and flood-prone landscape on top of telephone poles, with exterior stairs supported by recycled automobile tires, and an exterior clad in oak shingles cut from wooden shipping platforms; the Sanders-Dudley “Rammed Earth” House, constructed from a cement-soil mixture that hardens into a kind of man-made rock; and the Bryant “Hay Bale” House, whose twenty-four-inch-thick walls are formed by bales of hay covered with concrete. The “Hay Bale House” also has a separate smokehouse, built for a total cost of $40 out of broken concrete provided by the Hale County Highway Department, and a roof of salvaged road signs.

Samuel Mockbee died of complications from leukemia in December 2001. Winner of a MacArthur “genius grant,” he was also posthumously awarded a gold medal from the American Institute of Architects, joining previous recipients Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan, Le Corbusier and Louis I. Kahn. He believed that “everybody wants the same thing, rich or poor…not only a warm, dry room, but a shelter for the soul.”

Courtesy of Joel Sternfeld and Luhring Augustine

©copyright Joel Sternfeld