Guilhem Eustache. Fobe House

|

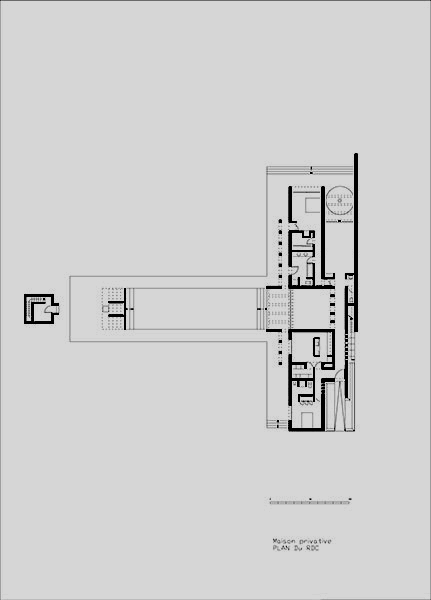

Home during the construction I have visited Morocco on many occasions over the years. The country immediately bewitched me. And the three Moroccan projects I´ve worked on to date are certainly fed, to varying degrees, by all the images and impressions I´ve accumulated during my stays there. The work of the principal architects, painters, sculptors, conceptual artists or filmmakers of all periods and all schools have had varying influences on my work. A detail of a Giorgio de Chirico painting, stumbling upon the Fez dye baths one early morning, a tracking shot in an Orson Welles´ film, discovering the Jantar Mantar site in Jaipur might all be conscious or unconscious sources of inspiration for me. All of the impressions we carry around with us – some of them for a very long time – eventually slip into our work. It’s a very mysterious process. It´s very difficult for me to pinpoint my precise architectural or artistic influences, where this project is concerned. So I’m always surprised when a journalist makes those very astute connections between my work and the work of one of those artists. Although, according to Hegel, architecture should be considered the first among the arts, my intervention is narrative – a more cumulative and pragmatic process than a conceptual one. The design of the FOBE House The main difficulty was to define the project with the client. Originally, we had planned to build three houses on this site. The project was gradually reigned in to the smallest of those three houses, in order to preserve the field. My client then informed me that he had purchased a second, larger plot of land (5 hectares) that was similar in nature but closer to the Atlas, which could accommodate the other two houses. Extensive analysis of the site is always essential. Its orientation to the sun, its size, shape, access, the best points of view (toward the horizon or neighboring homes) and any potential problems all necessarily impact upon one´s architectural choices. Observing the site convinced us to limit any built-up areas, in order to preserve the wildness of the land. The over-all design of the project grew out of the topology of the terrain. The main building was positioned in the center of the plot and the keeper’s house and garage, on the edge closest to the road to Marrakesh. The eye moves, when the perspective opens, gradually revealing the various elements that constitute the house. In the distance, we see a white square. As we move closer, it becomes a cube, a white wall, a tube. Then we discover openings… But another white rectangle turns out to be a flat wall and a small triangle, a pyramid. It is quite exciting to captivate the visitor, to suggest a vertiginous rise of steps, a plunging view into space. Or a pan across the landscape may eventually dissovle into a zoom towards the infinite, as you slowly move forward. The construction of the Fobe House The atmosphere that you feel when visiting the Fobe House has gradually taken shape over time. There were two distinct phases in the design and construction of the whole. Then we added a few details to the main house that were missing - the laminated stairs rising from the small pool and mounting all the way up to the roof terrace, all the paths and outdoor terraces that “float” 50 cm above the natural ground level, and finally the stairs/bleachers at the foot of the swimming pool. When the main house was first designed, we had no idea what the final result would be. We moved toward it unconsciously. The evolution of the project triggered our architectural choices. I could list all of our intentions for each structure, each architectural choice, each detail. But that seems a bit daunting. Each square meter was intensely discussed and debated, thought through and constantly reworked, so as to meet the client´s expectations. When the plans became clearer, evolving over time, the “right” (sharp and precise) choice became increasingly rare. Our possibilities were narrowing. By that point, we had the strange feeling that the house was choosing its own destiny. The project eventually nourished itself by keeping to its own logic. Technical details adopted to cope with the weather, hot temperatures, etc. The owner had grown up in Saudi Arabia and Dubai. His mother, who currently lives in the house, is an Egyptologist. She had worked on archeological excavations in Egypt´s Valley of the Kings, for the Brussels Archaeological Museum, in the 1960s. The techniques adopted to respond to the particular climate of the region are those commonly used and proven in the Maghreb. We chose to use local materials, primarily for rational, economic reasons. Overly sophisticated solutions and imported materials – often demanding tedious implementation and expensive maintenance – were on the whole rejected. There is, on average, between 10 and 20 days of rainfall per year in the region. There may be two major rainstorms each fall, which could flood the land. For that reason, we followed the advice of the Moroccans and elevated all buildings by nearly 50 cm. The land is on the edge of the area upon which constructed it allowed. Beyond it, that endless Atlas Mountain landscape stretches out in the background. On a clear day, it is quite breathtaking. This flat, barren desert land is full of hidden riches (with precious water lying less than 40 meters underground). It allows for clear visual connections between the separate buildings, the horizon and the earth itself. The smallest wall in the distance is magnified in this lunar landscape. Views of the snow-covered Atlas Mountain range emerge on clear days, from October to May. The final orientation of the house stems from that desire to see the Atlas, which has always haunted the client. He chose this land, near Marrakech, primarily for its stunning views of the mountains. We all worked together for the ideal positioning of the main house on the land. But it was the client alone who finally decided on the exact positioning of the house, to the exact degree. The end result is a compromise between climate considerations and the desire to have the most beautiful views of the Atlas from the living areas. To combat the heat, we created rooms with very high ceilings and double walls. Leaving an air pocket between the two walls made drafts possible, by increasing the openings to the outside. We created a winter living space and a summer lounge. We positioned concrete sun breezes in front of most of the openings, which work best when the sun is at its highest position in the sky, during the hottest hours of the day and the warmest season of the year… Using light colors, placing a small pool of water by the entrance, and building a large swimming pool also afford the house a breath of coolness. The most pleasant period of the year is between October and April. Winters are very mild. Temperatures are, on average, between 20° and 23° Celsius at mid-day, allowing for outdoor lunches. However, as in all desert climates, the nights are quite cold and temperatures can drop to 4° to 5° Celsius. Summer temperatures hover around 40° Celsius in the shade, at the warmest hours of the day. But they can even go up to 44° to 45° Celsius on occasion. The hottest months are between June and September. The two bedrooms are the only rooms that are air-conditioned. It is a reversible system, which also allows for heating during the coldest winter nights. Heating is used only in the two bedrooms at night, approximately 10 days per year and principally during the month of January. In addition, there is a fireplace in the master bedroom, as well as in the keeper’s house. http://www.guilhemeustache.com Biography Morocco: Land of cinema The list communicated by the owner of the Fobe House. Some great films made in Morocco (shot in part or entirely there) and which are often historical films: – « Lawrence of Arabia » by David Lean; – « The Sheltering Sky » by Bernardo Bertolucci; – « The last Temptation of Christ » by Martin Scorsese (shot 10 km from the Fobe House); – « Kundun » by Martin Scorsese (Shot in the Atlas Mountains); – « Black Hawk Dawn » by Ridley Scott; – « Alexander » by Oliver Stone; – « The Man Who Knew Too Much » by Alfred Hitchcock (shot in part in Marrakech); – « Othello » by Orson Welles; – « Kingdom of Heaven » by Ridley Scott; – « Troy » by Wolfgang Petersen; – « Babel » by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu; – « Des Hommes et des dieux » (« Of God And Men ») by Xavier Beauvois. There is a mythology of cinema in Morocco. The country and its landscape have served to bring to life some of the great myths, stories and cultures from around the world.

|